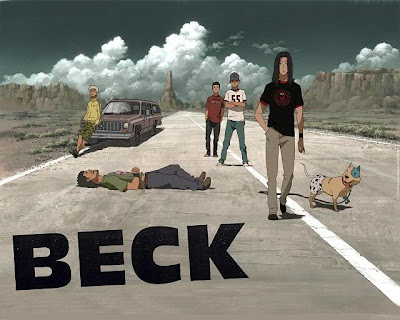

Beck has surprised me. It's different from other anime series in that it follows a band trying to make it in Japan and beyond. It has a heart that doesn't start beating until a couple episodes in, or maybe even further than that. It has its cast of characters, each unique with their own personality. Not one character feels like another, and although some may root for a favorite, I did not until closer to the end. Instead I found myself rooting for the band and the characters who make it up as a whole throughout the series.

Beck, also known as Mongolian Chop Squad... Wait let's hold on right there. Just so everyone knows, Mongolian Chop Squad is the name of the band in America. A young boy named Koyuki enters Junior high with only a couple friends. He's a bit awkward and shy, until one day he meets Beck (the dog) and his owner Ryusuke.

Ryusuke has been in bands before and has a rivalry going on with a former bandmate/friend. Trying to form a new band, he eventually inspires Koyuki to pick up the guitar and learn. Although Ryusuke can seem harsh towards Koyuki at times, he notices Koyuki's efforts and lets him into the band. It's named "Beck" after his dog.

Other members of Beck are the cool martial arts punk rapper Chiba, the mature bassist Taira, and the easy-going drummer Saku. Including Koyuki and Ryusuke, they come together to try and create a new sound in Japan that's both rock and punk.

Koyuki first learns to play the guitar by swim-teacher Saitou. He's absolutely insane and a pervert to boot, and I'm pretty sure he has multiple personalities or something... At the pool he's a hard ass who will push any student to their breaking limit, but at home he's quiet and calm.

Saitou teaches Koyuki how to play and Koyuki repays him by helping out around the house by moving boxes and such. Basically, Saitou teaches Koyuki out of his own will and is a great example of a character that doesn't just care about himself.

One of the best story elements that I enjoyed with Beck is its love story. It's not really love, though, as it follows Koyuki and the girls who enter his life. There are three in particular, most especially Ryusuke's sister Maho.

Maho shows interest in Koyuki and he instantly gets pulled into a series of uncomfortable situations. Because Maho and Ryusuke lived in America for a long time they know English, and have English-speaking friends. Koyuki gets lost in translation as Maho's friends tend to disregard his Japanese presence.

As with any teenage relationship there is conflict and feelings get hurt. For a time things seem to go well between Maho and Koyuki, and she completely supports him and Beck up on stage. Yet eventually a famous actor comes into the picture and gets a little close for comfort according to Koyuki. He gets jealous and pushes himself away from Maho.

He hangs out with other girls thinking Maho really doesn't want anything to do with him, which leads to more conflict. Oh the teenage love! Koyuki and Maho separate apart and come together again, with one such moment caught in an awkward sleepover.

The creators of Beck really did a great job at not pushing the relationship stuff too much. You sit and watch the story unfold, and although at first I wanted more romance, that's not what this anime is about. If you look at it from Koyuki's perspective, this is a coming-to-age story about a young boy as we follow him into his high school years. If we look at it from Beck's perspective it's a story about band members struggling to come together and make it big, encountering a series of challenges along the way.

If there's one element of the story I really didn't care for, it was that of Ryusuke's guitar "Lucille" and the consequences surrounding his possession of it.

Sure it brings in a nice blues element to the series, but I never felt as if Ryusuke was truly threatened by the bad guys from America. Relationships and real-life conflict were much more believable than gangstas roughing up Ryusuke and at times unnecessarily threatening him with a gun. Really? Maybe it's more believable in the manga.

Enjoying teenage drama and serious relationship stories in general, of course I like Koyuki and his story more than the other characters. At heart, he's just a teen trying to find his place in the world, and maybe trying to figure something out with Maho :)

Beck is incredibly commendable in animation quality and style and. It honestly looks great in so many scenes I often wondered what the budget for the show was. Some series don't take that risk in animating constant new locations and instead craft the plot to familiar surroundings. Yeah that may work, but when creators go that extra step it really stands out. The band plays at a range of live stages, we follow Koyuki and Saku at school, and other locations take presence throughout.

I may not be musically-inclined myself, but musical artists can certainly find something to enjoy. One of my friend's who is a musician told me that no, the fingering isn't correct all the time when the characters are animated. But sometimes they are and that gives a feel of authenticity. It also gives me the sense that the animators did their best to replicate live playing in animation, something that's incredibly difficult to do. Just a a look at the quality of detail in a guitar shop for example.

And although Beck is the kind of band I don't really listen to that often, I eventually found myself humming along and sometimes singing along! It's seriously that addicting! I think it's also the anime forming a relationship with the audience. I don't know that much about musicians, but after some research I discovered the manga and anime are chock full of influence and homage by and for many artists. Some are obvious like Freddie Mercury, John Lennon, and Kurt Cobain, but the series is lined with at least 30 other references.

Of course the soundtrack is amazing, and it's always great to hear Beck perform. The better they get live, the easier it is to root for them. One of my favorite songs for the series is "Moon on the Water", especially when Koyuki and Maho sing it. It's just a beautiful song, originally sung by the Beat Crusaders.

This brings me to one of the most interesting elements of Beck. The Japanese voice actors attempt to sing in a mixture of English and Japanese, usually resulting in Engrish. The translations are mostly accurate and being a primary speaker of the English language myself, it's very easy to notice. It's comical at first, but then it becomes a part of the show. Even the opening theme "Hit in the USA" has the line "I was made to hit in America", but I sang along anyways and I think it's awesome. I hear the folks over at Funimation cleared up the translation when they dubbed it in English, even rewriting the songs so they made sense in English. This is very interesting and I've yet to check it out, but the English voice actors also sing! So props to them for putting in the extra effort.

Beck is a series that forced me to go a little out of my comfort zone with anime, but I'm really glad I did so. It might've taken 10 episodes for me to really connect with the story and the characters, but once I did I knew it had potential to get even better. The character-driven story is superb and makes for a good time, and with music at the constant background it appeals to a larger audience. I don't know how successful Beck was in the United States, but I remember hearing about it when it was released. Probably due to the redubbing or something and people complaining. But hey, that release is hard to find now and even the re-releases don't seem to be in print... It was on Hulu, Funi's Youtube, and AnimeNewsNetwork, but just recently they took it down from streaming. If it comes back to streaming check it out because it's totally worth it!

As Beck (the dog) would say: "Woof!"

-Jared C.